|

Late Winter

1989 and the Coming Spring

The New York

Times often visited the Blackhorse Regiment to measure the

morale and check on the mission of the 7th Army in Germany.

The article below, from early 1989 reports a re-armed force

ready to do its job despite the privations of being so far

from ho me in expensive Germany. In many ways, that day in

1989 echoed the past; despite more and better equipment,

improved training and morale, troopers were still patrolling

along roads and trails adjacent to East German barbed wire

just as they had in 1950. But there is also that subtle

feeling of possible change to the status quo. me in expensive Germany. In many ways, that day in

1989 echoed the past; despite more and better equipment,

improved training and morale, troopers were still patrolling

along roads and trails adjacent to East German barbed wire

just as they had in 1950. But there is also that subtle

feeling of possible change to the status quo.

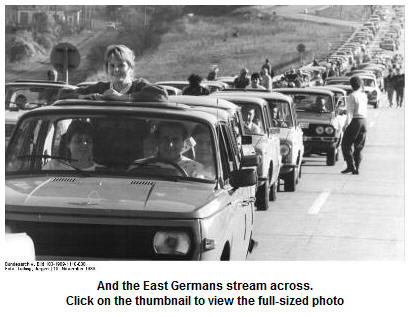

With

Gorbachev leading the Soviet Union, a new style leader was

at the helm and for millions of Europeans and the troopers

at Point Alpha, the 1st Squadron Border Observation Camp,

maybe there was room for change.

Who could

have imagined that nine months after this article, indeed

everything on the border and soon after, with the Blackhorse

would be so dramatically different.

On the

Central Front in Germany, Quiet Life and Good Duty for GIs

SERGE

SCHMEMANN

Special to

the New York Times

February 27,

1989

FULDA, West

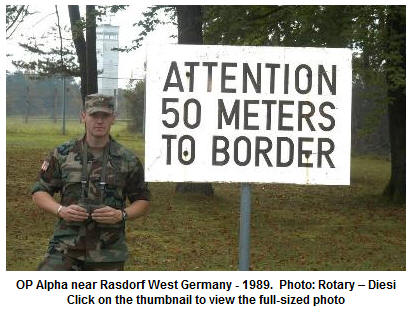

GermanyŚ Had the Russians invaded the West that day, the

American Army sergeant perched with elaborate binoculars on

the watchtower of Observation Post Alpha could have been the

first to spot them.

For a few

hours, his assignment was to stand watch at the Fulda Gap,

where the East juts farthest into the West and so, in

theory, the corridor through which invading Soviet tanks

would slice into Western Europe.

But the

central front was quiet that frosty day, as it has been for

the 44 years since Gen. George Patton drove Hitler's armies

back through here.

''I've never

seen any Russians,'' conceded the young sergeant, David

Rinehart.

Unlike the

Americans, who patrol right up to the line, Soviet troops of

the crack Eighth Guards Armor stay out of sight, leaving

day-to-day patrolling of their side of the divide to the

East Germans, who peer at Alpha from a watchtower 300 yards

away. Frontier and Symbol

In any case,

the Russians have no evident intention of attacking these

days, and even if they did, American satellites would spot

the movement long before the first tank would come within

sight of Alpha.

But even if

the strategic significance of Alpha is moot, it was clear

that the border post played a central symbolic role for the

11th Armored Cavalry Regiment, which is responsible for this

228-mile stretch of the border, as for some 350,000 American

service personnel in Europe.

''We call it

the frontier of freedom,'' said Capt. Bart D. Nolde at the

start of a drama-packed briefing at 11th Armored Cav

headquarters in the picturesque city of Fulda, about 10

miles west of Alpha.

Soldiers

moved about in full field gear, officers wore side arms, and

when a helicopter arrived with a visitor, troops lay prone

with M-16's at the ready around the landing field to

''secure the landing zone.''

Yet as a

symbol of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization's

traditional doctrine when the strategies and presumptions of

the alliance are being buffeted by shifts in global politics

and public perceptions, by new winds in Moscow, by a

quickening momentum in disarmament and by the exigencies of

shrinking budgets, Alpha may also be a threatened outpost.

New

negotiations on reducing conventional forces are scheduled

to open between NATO and the Warsaw Pact in Vienna on March

6. In Washington, the Bush Administration has already

announced the closing of several domestic military bases as

a prelude to cuts in defense spending.

In West

Germany, the public is showing ever greater irritation at

the concentration of foreign troops on German soil and at

the sense that the land is still under the vestiges of

military occupation.

And from

Moscow, the peace overtures of Mikhail S. Gorbachev, the

Soviet leader, have divided the Western allies between those

- predominantly in Washington and London -who would wait and

see how the economic changes in the Soviet Union fare before

making any modifications in Western defenses, and those -

most notably in West Germany - who believe the West should

actively encourage Mr. Gorbachev.

Is Gorbachev

Serious? Seeing Is Believing

Such notions

are not widely shared among the soldiers who stare daily

across the broad no-man's land - once the border of the

Kingdoms of Prussia and Saxony - with its three parallel

fences stretching the length of the inter-German border,

obviously designed more to keep East Germans in than the

Americans out.

A landmark at

Alpha is a white birch cross at the foot of the watchtower,

where an East German farmer was fatally shot one Christmas

while trying to escape with his son.

''When we

start seeing fewer coming over, I'll believe Gorbachev is

doing something serious,'' Captain Nolde said.

From a purely

military standpoint, trying to stop Soviet invaders at the

border would be foolhardy, since the attacking forces would

have the advantage of surprise and mobility.

But then the

American military's function in Europe has long been a

shifting blend of firepower, politics and bluff.

A Show of

Resolve And a Display of Force

About a

quarter of West Germany's population lives within 30 miles

of the border, and the mission of the 11th Armored Cav - the

elite ''Blackhorse,'' with 4,400 soldiers, state-of-the-art

Abrams M-1 tanks, Bradley armored combat vehicles and attack

helicopters - is to show both the Russians and the West

Germans the determination of the North Atlantic allies to

protect every inch of the West.

That forward

defense doctrine has been fundamental to NATO since the

alliance was forged 40 years ago, and it is one reason that

the United States and its allies have contributed to putting

on the central front the heaviest concentration of military

firepower ever massed in peacetime.

While debates

on military doctrine, the ''Gorby factor'' and the new

German assertiveness swirl through Washington, Bonn and

Brussels, for the soldiers secure in a transplanted America

of PX's, fast-food places, movie houses and Armed Forces

Network television, only the vagaries of exchange rates mar

a closed world that otherwise has never been so good.

Hitler's

Strongholds Now Have New Tenants

Theirs is a

unique archipelago of 800-odd posts scattered through

central and southern West Germany, ranging from tiny depots

in the back hills of the Rhineland to large headquarters

complexes in Frankfurt and Heidelberg and sprawling air

bases like those at Ramstein or Hahn. Most were bases taken

over by the United States Army from Hitler's defeated

Wehrmacht at the end of World War II.

In the 43

years since, these islands have coalesced into an outpost of

Americana. Ringed by cordons of pizzerias, used-car lots,

bars and video-rental shops, the bases and the families that

people them - typically Americans from small towns - have

become a familiar and commonplace fixture of modern German

life.

''When we

were young, the 'Amis' were the ones with real money, who

could afford the fuel for big cars,'' recalled Ludwina Otto,

a German woman in her late 20's who grew up near the Hahn

Air Base and eventually married an American airman. ''We

thought they were loud and wore baseball caps and checkered

pants and sneakers, and their kids had no discipline and

they never spoke German.''

The

stereotypes still hold, with the notable exception that the

Americans are no longer the ones with money. And the main

effect of the rise of the German mark has been to make the

217,000 G.I.'s more dependent on their own archipelago and

isolated even more from the ''host country.''

G.I.'s Are

Accepted If Not Quite Loved

In general,

there is no evidence that the irritation increasingly voiced

by West Germans over the concentration of men and arms on

their soil, or more broadly the sense that they are still

somehow occupied, has translated into overt

anti-Americanism. Even as German irritation over low-flying

jets or the damage from tanks on exercise has grown

considerably more vocal, the sentiments rarely extend to the

G.I.'s.

Some taverns

near American posts display ''Members Only'' signs to keep

out G.I.'s, but for the most part the soldiers are welcome

at the bars and many village festivals, and many single

G.I.'s still find German spouses. Even those Germans who may

be fiercely opposed to new American missiles or screeching

training flights pay little heed to the American corporal in

camouflage fatigues pushing his luggage through Frankfurt

Airport, or the Plymouth with ''U.S.A.'' license plates

cruising the Autobahn.

''You have to

distinguish between military exercises, which nobody wants,

and the Amis, who are part of the local scene,'' said Karsten Voigt, a spokesman on military affairs for the

Social Democratic Party in Parliament.

''I live near

an American base in Frankfurt - you see them all the time,

in the streets, in the subways, they're about 5 percent of

the population, but they're part of a different world. They

live in their own isolated villages, and normally they keep

to themselves.''

Germans of 2

Minds On the U.S. Presence

The German

attitude seems to reflect an ambivalence that comes through

in public-opinion polls that show both a pronounced

enthusiasm for Mr. Gorbachev and a matching desire to remain

in NATO.

''What we're

seeing here is a wish to have their cake and eat it too

among the Germans, a desire to enjoy their prosperity and

security without the hassle of low-level flights and ripped

up cornfields,'' an American diplomat said. ''But it's hard

not to sympathize. This is a country the size of Oregon, and

all these troops are roaring around.''

The ''Amis''

may not seem as rich to the Germans as they once did. But

within their own world, it has been a long time since they

were so well off.

By common

consent, the eight years of the Reagan era have been a

windfall for the military, with the introduction of some 400

new weapons systems.

In the new

tank shed at Alpha, crews tinker with six Abrams M-1 tanks,

the cutting edge in armor. Back at the headquarters of the

11th Armored Cav in Fulda, new Bradley armored fighting

vehicles stand alongside broad new ''Hummer'' (Highly Mobile

Multipurpose Wheel Vehicle) jeeps. Armored Cav in Fulda, new Bradley armored fighting

vehicles stand alongside broad new ''Hummer'' (Highly Mobile

Multipurpose Wheel Vehicle) jeeps.

The new sheen

is not restricted to the hardware. Old barracks glow with

new paint and insulated windows. The bunks are thick and

comfortable, the mess hall has a salad bar and a burger

counter, the roads and parking lots are smoothly paved.

To be sure,

as the unit designated to absorb the first blow of the

Russians, the 11th Armored Cav has always had it better than

the soldiers on the hundreds of posts, large and small,

tucked away in the hills and forests of Bavaria and the

Rhineland.

There is a

conscious elitism - a military salute is accompanied by a

shout of ''Blackhorse,'' the unit's proud symbol. The

commanding officer, Col. John N. Abrams, is the son of Gen.

Creighton Abrams, the late commander of United States forces

in Vietnam, for whom the new M-1 tanks are named.

But even the

smallest depot the Hunsruck woods south of Frankfurt has

benefited from the Reagan spree.

Army on the

Mend: Soldiers Find Stability

''Before

Reagan, morale was incredibly low, drugs were common,

equipment was rotting away, soldiers lived six to a room in

rooms built for four,'' recalled John Kominicki, who served

in the Army in Europe before becoming city editor of Stars

and Stripes, the newspaper for G.I.'s in West Germany.

Now at V

Corps headquarters in Heidelberg, officers cite rows of

statistics to demonstrate the recovery of the Army from the

wounds of Vietnam and neglect - 94 percent of soldiers have

high school degrees, drug abuse is way down, re-enlistment

is high, spending on services is sharply up.

Despite the

fallen dollar, the Americans have remained a major source of

income for Germans living near an American base. Many

Germans work on the bases or at businesses keyed to the

Americans. More than half the soldiers are married, and many

bases, unable to keep up with the demand for family

quarters, are sending many more soldiers and airmen out to

live ''on the economy.'' German landlords, keenly aware of

military housing allowances, charge the ''Amis''

considerably more than they charge Germans.

April 2016 |