| |

War Plan 1951: Railway Denial Mission

From the very first days of the Cold War in Germany, barriers,

obstacles and special missions for the limited US Army Engineer

units in Germany were central to war planning. It is a largely

untold story and a chapter takes place in Bad Kissingen.

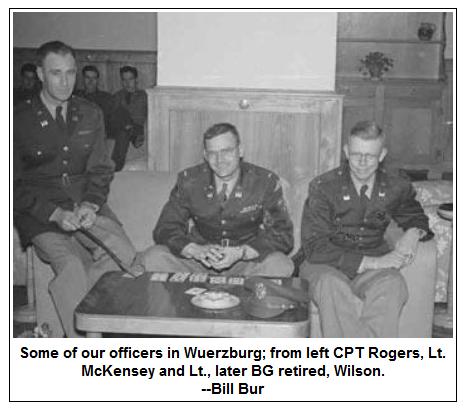

Major portions of the following article appeared in The Army

Engineer Magazine, Sept - Oct 2002 issue, as written by Col (Ret)

Ray S. Hansen and BG (Ret) Robert M. Wilson. They were troop leaders

with first hand experience with the mission. If anyone would like a

photocopy of this article, please contact the web master and we will

send it along. They also generously provided additional information

by telephone and e mail. Bill Burr, a trooper in one of the key

engineer units, provided great recollections and photos. Special

thanks to the family of Col (Ret) John V. Parish, who also provided

photographs.

1st Platoon, Company C, 18th Engineer Battalion: BK and the Big

Bang

Col (Ret) Hansen and BG (Ret) Wilson:

"NATO allies were ill prepared to resist a Soviet attack, if it came

in those first days of the Cold War. Germany was still an occupied

country, and had no armed forces. British, French and US units in

Germany had been organized for occupation duties and not for defense

against a former ally. The only major US units were the 1st Infantry

Division, the US Constabulary and the 6th Infantry Regiment in

Berlin. Engineer units were limited at best and the still powerful

Red Army kept 20 plus divisions in East Germany, with ten more

behind those and a total force of 2.5 million troops."

"US planners realized that at best, the

current allied force could hope to wage a delaying action in the

event of attack and the Rhine River would be a major obstacle in the

planning. Further, they realized that the Soviets relied heavily on

rail for logistics and heavy equipment. Massive interdiction of West

Germany's east - west rail system would be required to impede

movement of bridging equipment for Soviet crossings of major rivers

such as the Main and Rhine. For this vital mission, the Pentagon

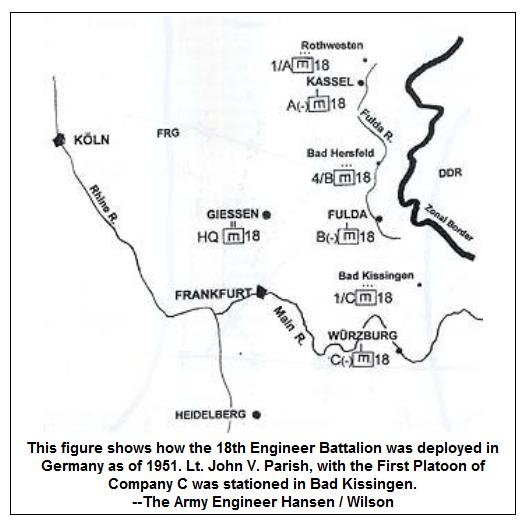

ordered two units specially created and deployed. The 18th Combat

Engineer Battalion was organized in Germany in 1950, the 485th

Combat Engineer Battalion was called up from Reserve status, fitted

out at Fort Belvoir and arrived in Germany in 1951."

When LTC Spurrier led the 2nd Recon Battalion from Schweinfurt to

Bad Kissingen in 1951, one of the other units that also soon moved

to Manteuffel Kaserne was the 1st Platoon, Company C, 18th Engineer

battalion. Their mission was simple, to study the assigned railroad

bridges and tunnels in their sector, a corridor running southwest

from the border towards the Main River and beyond and develop

detailed plans to, in the event of war, destroy them with

conventional explosives. From Rothwesten in the north to Wuerzburg

in the south, other platoons and companies of the 18th were

similarly analyzing their own target lists.  Col (Ret) Hansen was located in Fulda and BG

(Ret) Wilson and Bill Burr were in Wuerzberg with the 18th and their

experiences would certainly be similar to those of the engineer

platoon in BK. Their recollections help set the scene in Germany as

the denial mission began. Col (Ret) Patrick D. Tisdale MD and Harry

W. Thibeault tell the story from the Bad Kissingen perspective.

Col (Ret ) Hansen and BG (Ret) Wilson:

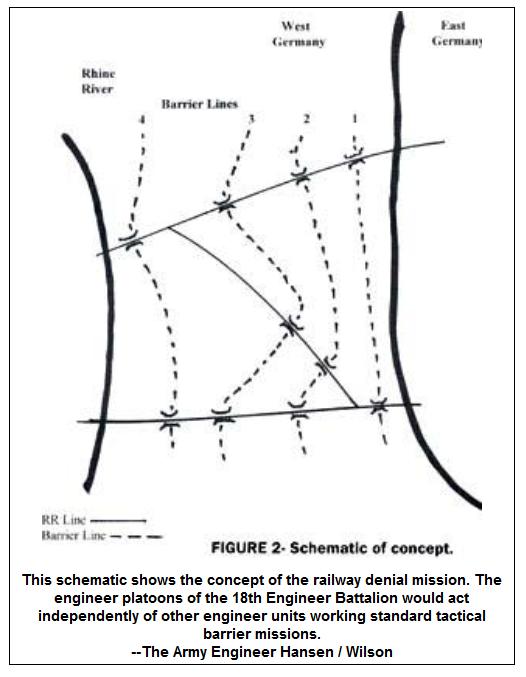

"In late 1950, the 555th Engineer Combat Group prepared the

Strategic Railway Denial Plan and assigned missions to the two

battalions. Sufficient targets were identified to form four

successive ' barrier lines '. Not lines of obstacles in the normal

sense, these were barriers to rail movements. They were laid out to

insure every route from the east to the Rhine would be cut by at

least four targets. Later, 7th Army added twelve targets not on

railways."

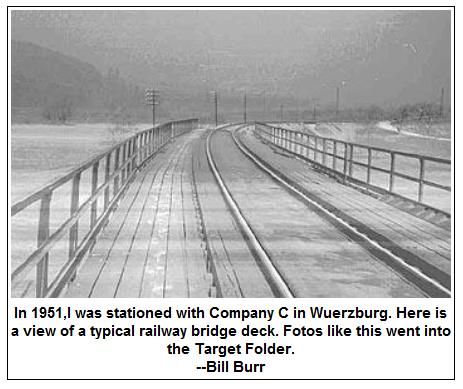

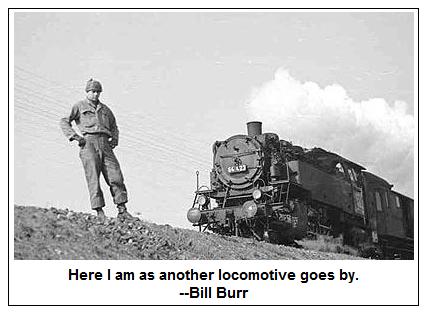

Bill Burr:

"I was a basic engineer and in the Constabulary upon arrival at my

first duty station in Germany, July of 1950. (Korea broke out in

June while I was in basic training just at the end of our cycle). I

wore the ' Circle C ' patch and all the leather for about 3 weeks.

Then we took off the Circle C and replaced it with a ' 7 Steps to

Hell ' patch (7th Army). From there we were taken to Kaufburens '

Fliegerhorst Kaserne ' . We trained there for a short time and a

number of us were sent to Murnau USAREUR Demolition School, from

which I still have my diploma. I collected my Hazard Duty Pay for

the whole time I was in the company. (( Company C, 18th engineer

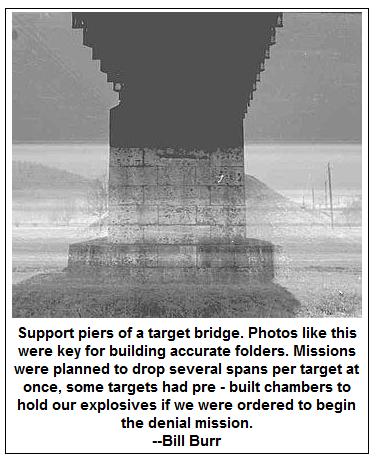

Battalion in Wuerzburg )) In the early days we inspected each target

bridge and I took photos for the target folders. I would take them

to the Service Club, develop them and make matte enlargements and

add the dimensions of the abutments, girders etc. The other men

sketched the sections and put down the dimensions."

Col (Ret) Hansen and BG (Ret) Wilson:

"Each bridge and tunnel had a comprehensive target folder. It

contained maps and sketches of exact location, and charge details

such as size, placement and firing mechanism. Individually

classified CONFIDENTIAL, and as a group SECRET, they were kept in

company safes. We suspect most squads could do their jobs from

memory."

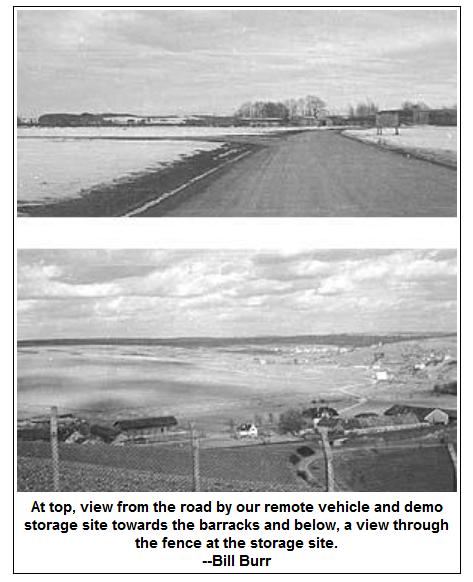

All of this required great amounts of explosives and equipment

necessary to move it. The allocation was in the order of 100 tons

per company split between tetryol, composition C - 3 and TNT. A

small fleet of trucks, trailers and jeeps was assigned to each

platoon; they were authorized to exceed normal weight and cube

limits to transport the loads. All the vehicles were kept loaded and

parked in special, secured remote sites. While each platoon had

sufficient equipment to move their explosives in a single lift,

there were additional stores at Wetzlar, Hanau and Munster. There

were no significant accidents but both Bill Burr and CWO 4 (Ret)

Charles Wright recall close calls.

Bill Burr:

"I can remember one day (my secondary MOS was driver of the HQ

platoon's 3/4 ton ).

We had been called out on alert, my W/C was in

ordnance for some repair which landed me as a passenger in the rear

of a 2 1/2 ton truck. (No explosives on board). In Nuremburg (I

believe) the convoy stopped. After a 10 minute wait, we started to

move again at a fairly high rate of speed. We passed another 2 1/2

which was off on the side of the road. That was one of the fully

loaded

demo. trucks. The guy driving was an assistant driver, with no

driving experience, other than barely passing the test and he had

never driven anything prior to joining the Army. He had failed to

release the emergency brake, which had caught fire. The CO (CPT

Rogers), the First Sgt. and the driver were frantically throwing C-3

satchels off the back of the truck onto the side of the road. As

this was happening, an EES (European Exchange Service) panel truck

came by in the opposite direction, saw the commotion and stopped.

The driver brought out an old pyrene fire extinguisher and proceeded

to help put the fire out. Had that man known what was in the truck,

I think he would have burned tires getting away from there. Needless

to say, if it had gone off, sympathetic detonation probably would

have taken the whole outfit and a good part of Nuremburg with it."

CWO 4 (Ret) Charles Wright, stationed in Fulda, recalled :

"We had a report of one convoy going through Gelnhausen and trying

to maneuver through those narrow streets when they lost sight of the

other trucks. The driver increased speed to catch up and reached a

fast pace as he rounded a corner, then he found the convoy stopped

and plowed right into an explosives filled trailer. There was

tetrytol all over the place. They cleaned the scene up and got the

trailer going again and made it back to Fulda."

Even in those early days of the Cold War,

consideration was given to not alarm the local population and what

must have been a disturbing scene, American GIs constantly standing

next to major railroad bridges and tunnels with clipboards and tape

measures, soon became a thing of the past.

Col (Ret) Hansen and BG (Ret) Wilson:

"On 17 March 1951, 7th Army issued an order prohibiting practice on

actual assigned targets. Neither real or dummy explosives were to be

placed, even under cover of maneuvers. Targets could be measured or

sketched only by small parties under cover of maneuvers."

Beyond the war mission, the companies and platoons also followed a

normal training schedule to maintain their engineer skills. To gain

access to the full set of engineer equipment, they had to closely

coordinate with the few fully configured engineer units in that part

of Germany. Construction and the standard field tasks for engineer

units plus the normal menu of individual soldier skills were central

features of this training. It is perhaps in this light that Lt. John

Parish in Bad Kissingen, was able to get his men involved with the

construction of the air strip at Reiterswiesen.

Harry W. Thibeault:

"I was in Bad Kissingen for 18 months, starting in 1952 and was

assigned to the demolition platoon. I was a driver and also had

explosives training. We kept the trucks and trailers fully loaded

and parked in our own separate area at the barracks. We guarded it

day and night. We also kept an empty truck by the orderly room door

or wherever the platoon was to carry us all to the motor pool fast

if there was an alert. I do remember working on some civil

construction projects for the Germans and the ' alert ' truck always

followed us. Our barracks was in good shape and there was a medical

platoon living in our area."

"We would inspect the targets now and then; I recall we had one big

tunnel that required explosives set in chambers at one end and also

in the middle. So, one day we are at that target looking at the

chamber in the middle and it was pitch black except for our flash

lights. The chambers had big steel doors that we swung open and

somehow in the dark, I tripped over a rail and fell against the edge

of a door. I hit me knee and I never felt such pain in all my life!

33 years as a municipal fire fighter and that one day in Germany was

the worst! I couldn't walk and they had to wheel me out of the

tunnel on a cart! The medics gave me a few days off until the

swelling went down."

"I recall that we had very limited over night field duty, our

mission was those trucks loaded with explosives so beyond

engineering work we did in town and regular training, there were no

FTXs. I also recall that the platoon integrated while I was there.

The Platoon Sergeant announced one day that it would happen and

said, ' ... there better be no trouble!'. There were some all black

engineer platoons in Germany that were broken up and each unit

received something like 10% of the unit roster, so we got three or

four guys. I guess it went OK, I don't remember any big trouble."

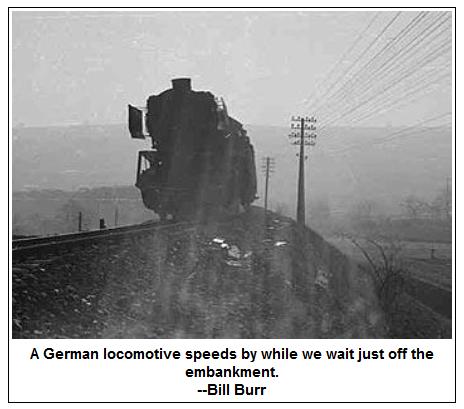

"BK was pretty and we did what soldiers do,

ran around, chased girls and bought some beer. One guy got paid and

got on a train out of town. Well, I guess he got in trouble and lost

his money so he started to walk back by following the railroad

tracks. You wouldn't think it but those German steam trains were

fast and quiet and they found the body sometime later. There was an

investigation to see if he was AWOL or what, it had to do with the

benefits to his parents. It was a sad story, but almost everything

else I recall from my Army job was good."

Col (Ret) Patrick D. Tisdale MD:

"I followed Jack Parish as the First Platoon leader of Company C ,

18th Engineers and it has been a very long time since I gave any of

this much thought. The junior officers in the battalion were rotated

around each year or so; I had time in Wurzburg, Bad Kissingen and

Fulda, some of the memories blend together."

"In BK, I lived in a hotel in town but cannot recall much about it.

I bought a really nice camera soon after arriving in BK to update

the target folders, took the photos and then gave the camera to my

Platoon Sergeant as a gift. I never was much for photography beyond

what was called for in the job. In general, I recall we were busy

and leave was almost unheard of if you were the Lt. or a senior NCO.

There really was a feeling that we would be called out to destroy

our targets at a moment's notice."

"Three targets remain clear in my memory. Near Bad Kissingen was a

large tunnel that was our responsibility. We were to destroy both an

end and the middle, explosives chambers were built and this target

required a great deal of explosives. We figured we could drive the

truck and trailer into the tunnel but this would be very slow so we

looked for alternatives. On another railway line, we found some

German ' right of way ' maintenance carts that were fitted with rail

wheels. They were ideal to load and then push by hand down the tacks

so ... we liberated them and hid them in the woods near the tunnel

entrance. Another target was a steel railway bridge that I recall

looking at first as a trained civil engineer. It was a beautiful

bridge, long and sweeping using just enough steel to bear the weight

of the trains from pier to pier. Because it was so carefully

designed, it was also a very easy target to destroy. Just a few

charges at the critical points and it would have dropped straight

into the river. In Fulda was a tunnel that ran across the border and

this was the only target that had been loaded with explosives and

under constant guard by an engineer squad."

Erwin Ritter adds the detail concerning the Fulda tunnel:

"Yes, between Schwebda / FRG and Geismar / DDR, was a 1066m long

railroad tunnel. The name was "Frieda-Tunnel". The tunnel is closed

now and the railroad does not exist any longer. The line was closed

in 1945, at the end of the war, because one of the bridges near the

border was damaged. In the 1980s the tunnel was filled up with

stones."

As more US troops flowed into Germany and "first battle plans"

became more refined, the mission of the "destruction" battalions

began to recede as new engineer units took over the denial and

barrier plans. In 1957, the 18th Engineer Battalion was deactivated

as a "demolition battalion". The 485th had departed two years

previous. The bridge destruction mission by the 1960s, became an

atomic demolition munitions story.

BG (Ret) Wilson:

"To the best of my knowledge, the engineer platoon in BK never

returned to the parent company in Wuerzburg. For as long as the

railway denial mission existed, there were targets near BK that

could not have been reached in time from Wuerzburg (C Company also

had another detached platoon, the 2nd platoon attached to A Company

in Kassel. They never returned either.) When the 18th was

inactivated in 1957, its personnel (except those due for rotation)

were reassigned to other engineer units in Germany. Probably a good

number of the 1st Platoon guys stayed right there in BK."

After leaving Bad Kissingen, Lt John V. Parish, later Colonel (Ret),

went on to a long and distinguished career to include service in the

Middle East, Vietnam, the USA and Germany. Col. (Ret) Patrick D.

Tisdale MD, left Germany for a stateside assignment at Fort Belvior

then went to medical school. He returned to active duty as a

physician and became one for the lead pediatric doctors in the US

Army over a thirty year career.

|

|