Of note, Army aircraft flight - following

procedures during this era were practically non - existent. This

was the beginning of the true Cold War but some procedures were

still in place from the U.S. Army Constabulary Period.

At fixed field locations, arriving or

departing pilots would sign in and out on a Constabulary Sign

Out Book which could be reconciled through the phones or radio

if necessary but even this simple system did not exist at field

locations. It was possible to fall “ through the cracks “ if no

one was carefully monitoring an aircraft departure and

subsequent anticipated arrival at another field site.

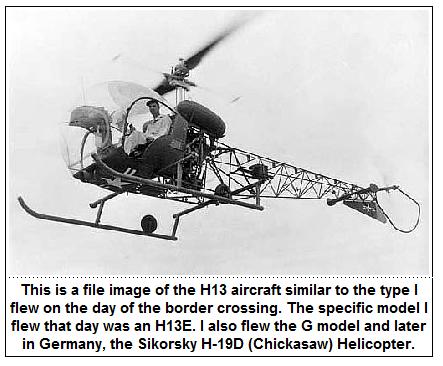

On the specific day in question. The

weather was not good but considered flyable. I picked up Herr

Kuehn and began the flight to Fulda. I elected to fly a compass

heading to the Fulda area and calculated the time of flight. I

planned to refuel at Fulda Army Airfield and then begin the

specific itinerary of Herr Keuhn’s inspection. In retrospect, I

should have been much better at the time honored traditions of

flying IFR ( I follow roads ) and was unaware that the magnetic

compass that I was using as the primary navigation aid had, if

fact, a 20-25 degree error.

I was following an east - northeast

compass heading and flying into a strong northwest head wind,

the combined affect of the compass error and the weather soon

had me much further south and east than my anticipated flight

plan. I would have caught the error had I been regularly

checking the roads and towns on my map with what we were

observing thru the bubble but, this was not the case. As heavy

snow showers further complicated the situation, I realized I was

disorientated and unsure of my location. As stated earlier, this

was well before all the navigational, radar and radio tracking

Army air traffic controls that would become so routine to

aviators a few years later.

One cannot be too proud to ask directions

and that is what we attempted to do. From the air, we spotted a

farmer and his ox cart and I set the helicopter down in an open

field to allow Herr Kuehn to find out where we were. I stayed

with the aircraft to study the maps, Herr Kuehn spoke with the

farmer. We naturally assumed we were still in West Germany;

sadly, this was not the case.

Captured

I guess if you’re going to be flying in

marginal weather with a bad compass and you become so lost as to

have to ask a German farmer for directions, you figure it

couldn’t get much worse. Well, it got worse.

At about the time that Herr Keuhn

determined we had crossed the border and landed in East Germany,

rumbling down the road towards us came a bus load of East German

border guards. At any other time of the day, the road would have

been just for farm use, but as luck had it, they were in the

middle of changing the guards so the bus was filled with troops

and we were truly in the wrong place at the wrong time. Looking

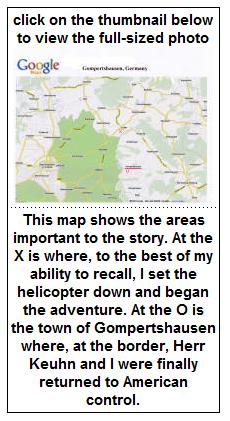

back at it, we were somewhere very close to the poorly marked

border in the rolling farm country to the southeast of Meiningen.

I looked up from the maps to see Herr

Keuhn being loaded into the bus and a group of guards

approaching the aircraft with weapons drawn. I shut the engine

down and was allowed to secure the blades with the tethers

before I too was loaded into the bus, a prisoner of the Cold

War. We were taken to their Headquarters.

Gone Missing - Search and Rescue

Operations

When I failed to show up at any of the

locations Herr Keuhn was anticipated at on 17 March, we were

reported missing and Army and Air Force units under the

direction of the 12th Air Force Rescue Service began a search.

Because of the bad weather and prevailing winds, they correctly

concluded that we should be in the near border area and by the

20th, concluded we had in fact gone d own in East Germany. While

U.S. Army and West German ground units continued the ground

search, U.S. Army Headquarters notified the Military Mission in

Potsdam, Berlin to contact their Soviet counterparts and request

assistance from their side in locating a crashed aircraft,

military pilot and West German civilian. We were now an

international incident.

own in East Germany. While

U.S. Army and West German ground units continued the ground

search, U.S. Army Headquarters notified the Military Mission in

Potsdam, Berlin to contact their Soviet counterparts and request

assistance from their side in locating a crashed aircraft,

military pilot and West German civilian. We were now an

international incident.

Russian Confinement

After a short time at the East German

Border Guard HQ we were turned over to members of the Russian

Army. We were taken to the HQ of an infantry unit in

Hildburghausen

and placed under armed guard on the second floor. Two

beds were brought into the room.

We assumed the room was intended as some

sort of information office, it was filled with Soviet

literature. The windows had bars but it was not a prison cell.

We had a good view of the Soviet military base, barracks area

and main gate. The immediate street below was used as an

assembly area for the Russian infantry platoons, traffic on the

street consisted of older lend - lease US built ¾ and 2 ½ ton

Dodge trucks. There was very little traffic through the gate, my

impression was that the town was off limits.

In spite of the run of bad luck, I recall

the humor of while watching Soviet troops standing in the rear

of a formation make snow balls and lob them over the heads of

the assembled troops at NCOs at the front. So much for their

discipline.

For the first few days there was no

attempt to interrogate either myself or Herr Keuhn. I came to

believe that no one in the unit spoke any English. On several

occasions, a Russian major escorted us on exercise walks on the

street in front of our building but nothing was said.

We were fed twice daily, on the same

schedule as the Soviet troops, the second meal was usually at

about 20.00 hrs. Our meals were the same as our guards, sort of

a thin meat broth with some vegetables and potatoes tossed in.

We were also given a bottle of cognac. We were also given a

checker board set, paper and pencils. Herr Keuhn and I passed

the time with checkers and playing the grid game of Battleship.

On the forth day of confinement, the

interrogators finally showed up and Herr Keuhn and I were

questioned separately. They seemed more interested in learning

personal information from me and appeared to accept at face

value, the story that I was simply ferrying the German national,

became lost in the bad weather and had by accident, landed in

East Germany. At no point did I feel threatened or intimidated.

The same seemed true for Herr Keuhn.

Meanwhile … Back in the West

While all of this was going on, events

were unfolding in West Germany. A German national who was

employed at the Coburg Officer’s Club located at the former

German barracks had been visiting family in the border area and

in fact observed from a distance, the landing and capture. He

reported this to his American employers and the story filtered

up the chain of command to the State Department. The Russians

still had not verified that we were being held or lodged the

expected complaint. In Berlin, the Soviets were formally

notified that the U.S. was aware that an Army pilot, West German

civilian and US helicopter were being held and that the

personnel were not injured at the time of capture.

Return to US Control

On the morning of 24 March, we were given

hot water, soap and razors. We figured something was going to

happen but because the English speaking Soviets were not around,

it became a matter of some speculation. Our personal belongings

were returned and we were placed into a sedan. Under armed

escort, we departed the Kaserne and drove off in an unfamiliar

direction. After driving about 25 miles, I could see the bubble

canopy of the H13 in the distance. It was under Soviet guard and

we were not allowed to approach further.

After waiting for approximately 30

minutes, several olive drab sedans bearing large American flags

on each front finder came down the road. Inside were U.S. Army

personnel from the Military Mission in Potsdam and a pilot and

crew chief to look after the helicopter. The pilot was Captain

Phillip Neary of Manchester, MA and the Chief was Sergeant Jack

Henderson from Fort Wayne Indiana, my home town. They were

assigned to the 6th Infantry in Berlin and were to check out the

aircraft and then fly it to Straubing in the West. I was amazed

that we were allowed to take the aircraft back into U.S.

control.

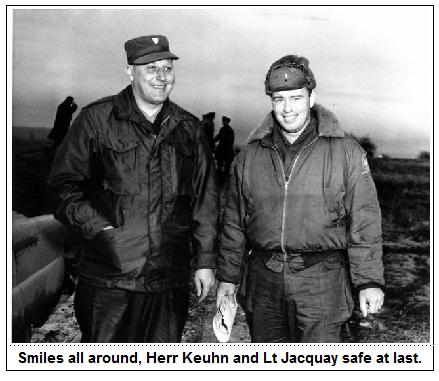

In due course, Herr Keuhn and I were

driven to an ad hoc crossing point along the border in the area

between Alsleben and

Gompertshausen, about 22 miles northeast of

Bad Neustadt. At the border, First Lieutenant Theodore S. Cohen,

HQ 14th ACR in Fulda and Captain T. J. Gigouard, Hq 7th Army

signed documents that they had received us from Russian custody.

It was 9.45 AM on 24 March 1955.

Herr Keuhn and I then were driven to Fulda

where a thorough physical examination occurred to confirm that

we were in good health and had not been injured while in Soviet

hands. 7th Army Aviation Section then flew us to Stuttgart -

Echterdingen airfield and then by car for a full day of

intelligence debriefing conducted by 7th Army personnel at

Ludwigsburg. At this point, they made it clear what we could and

could not say about the incident.

The Trip Home

The following day, Herr Keuhn and I parted

ways, each in our own separate Army sedan. I was being driven

through Stuttgart en route to Boeblingen when we suddenly heard

the wail of an MP siren. As we pulled to the side, an MP jeep

passed us leading a procession of two civilian cars. Much to my

surprise, as the cars shot by, I recognized my wife in the first

car and members of her family in the trail car. I asked my

driver to follow the group and we headed off towards the main

U.S. Army Hospital at Bad Cannstadt. When I finally caught up

with them, my wife was on the elevator on the way to the

Maternity Ward. That day, she delivered an eight pound 12 ounce

baby boy, my son Jeffery Robert.

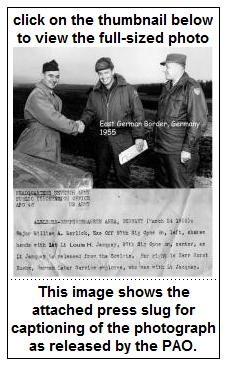

Press Conference

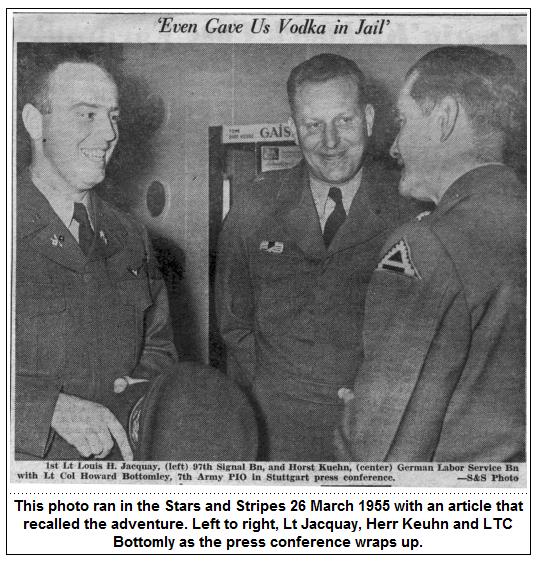

On 26 March, 1955 a press conference was

held at the Graf Zeppelin Hotel in Stuttgart. Herr Keuhn and I

were present and were interviewed by LTC Howard Bottomley, 7th

Army Public Affairs Office. I was quoted as saying, “ I am

grateful for the aide and assistance given to my family by

American friends

during my absence. “. I also thanked the

personnel involved in the search and rescue operation, my fellow

pilots who flew the border search missions and the men of the

14th ACR who conducted ground search operations in the border

area.

My Letter of Reprimand

The dust finally settled on this rather

exciting week in my life but not before it was punctuated by a

Letter of Reprimand signed by no one less than the Commander of

7th Army, Europe! Imagine, General Henry I. Hodes took the time

out of his undoubtedly very busy schedule to send me a letter! I

was reprimanded for exercising poor judgment in continuing to

fly the mission in such poor weather and for using an aircraft

not equipped for operations in such weather. The letter was

placed in my Field 201 file and removed upon my departure from

Germany at the end of my normal three year tour. I guess that

the Army needed aviators or the letter was not widely read, in

due course, I was promoted to Captain, integrated into the ranks

of the Regular Army and continued a long and exciting career in

Army aviation.