| |

We Command the Sun, the Earth and the

Winds

In mid summer 1945, two generals walked through American run

Bad Kissingen following a private lunch. Military police,

staff officers and aids keep a respectful distance as the

pair briefly enjoyed the promenade along the Saale River,

down the former Adolf Hitler Strasse, newly re - named as

Roosevelt Strasse and past the elegant Kur Hotels occupied

by the victorious Americans. This was not just another shot

out Kraut town - everything was frozen in time, intact -

little hint of the war beyond the one blown bridge.

Rain the previous night, but the sky had cleared and there

was a distant but growing rumble coursing through the

valley; storms again? The pair reached the reviewing stand

in the park area, climbed to the podium and brief remarks

were made to hundreds of assembled Army Air Corps personnel.

They were in loose formation and there were no invited

German guests. This was victory and this was a part of the

American celebration.

Binoculars were handed to the generals; one turned to the

other and made a sweeping gesture with his arm across the

blue sky as the rumble grew louder. Both men put in cotton

ear plugs, the noise was now so loud that normal speech was

almost impossible. First through parting clouds, a single

P51 fighter, following the river from the south. It cork

screwed a barrel roll maneuver just hundreds of feet above

the crowd and its shadow flashed, specter like across the

streets, along the walls and over red tiled roofs of the

town. The growing roar of approaching aircraft engines was

now deafening, the leafs trembled, the enormous sound

reverberated through the bodies of the assembled men, the

sky was clear and then the town sank into shadow, the sun

was blocked out.

Look to the Sky, We Darken the Sun!

Here are four brief New York Times articles and then the

associated stories that help illustrate the American

experience in Bad Kissingen during the first days of peace

in Germany. While most of us recall the town as an Army

garrison of cavalry and artillery units, in the immediate

post war period, the full power of the American Army Air

Corps was everywhere, they could darken the sun, they could

cover the ground and even predict the weather.

( I ) 40 Mile Air Parade to Mark Anniversary - New York

Times - July 30 1945

London, July 29 - an aerial parade forty miles long will fly

over the major European cities on Wednesday to mark the

United States Army Air Forces thirty - eighth anniversary.

Aerial exhibitions will be held over Britain, France,

Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany, with a special review

over Bad Kissingen, the German headquarters of the Ninth Air

Force, to be reviewed by Major General O. P. Weyland.

Approximately 900 planes will participate in the aerial

demonstration including 600 Ninth Air Force Thunderbolts and

Mustangs and Marauders of the Ninth, Twelfth and Twenty -

Ninth Tactical Air Commands. The planes will fly low over a

number of former air targets and other places in Germany.

The article concluded by recalling the plans for an air

power parade and exposition in Paris that same week.

>>>

As reported in the Times, the guest of honor at Bad

Kissingen, at what must have been a overwhelming and

frightening display of American air power, was Army Air

Corps Major General Otto Paul Wayland. He was being honored

by his former boss, the soon to depart commander of the

Ninth US Air Force, Lieutenant General Hoyt S. Vandenberg.

Both men were visionaries who made remarkable contributions

to the Army Air Corps, the victory in Europe and formation

of the early American Air Force. At Bad Kissingen, they met

to say farewell, toast their victory, celebrate American air

power and enjoy the show.

O. P. Wayland had an interesting career in pre war Army

aviation that featured varied flying and staff assignments.

Because of the comparatively small pool of aviation

officers, promotions were slow. Once the US entered World

War II, however, his career path suddenly blossomed and he

quickly rose to Brigadier General in command of a fighter

wing. In 1944, he took command of the XIX Tactical Air

Command in England, consisting of two fighter groups, the

100th and the 303rd with the primary mission of escorting

heavy bomber groups in raids over Germany and France.

While flying from England, the XIX began to receive new,

light and medium bombers as well as specially developed

fighter - bomber aircraft. The command was directed to

explore what was necessary, both in terms of training and

equipment, to more closely integrate aircraft support to

combat operations of ground units in the planned invasion.

Tentative plans were made and in mid 1944, with the invasion

of France, the XIX TAC was tasked with the direct tactical

air support of General Patton’s Third Army. To accomplish

this, Weyland now had 25 separate squadrons of fighter,

light bomber and reconnaissance aircraft supported by

battalions of ground personnel building airfields, repairing

aircraft and integrated into forward units as controllers.

The mission and tactics of the XIX Tac Air evolved once the

battle was joined in France. While air supremacy was still a

major concern, the grand experiment of close tactical air

missions flown in direct support of forward ground echelons

began in earnest. What had been discussed and experimented

on in England, became a standing mission for the command,

although surprisingly, the idea of close air support was not

immediately embraced by all senior air or ground officers.

The idea of using aircraft to attack targets that earlier

doctrine said should be engaged with field artillery took

some getting used to by commanders throughout the Army.

Wayland and the general officers who supported the doctrine,

knew that the most effective sales pitch was success and

when the break - out from Normandy was spearheaded with

close air support, detractors were silenced once and for

all. It was said that Wayland’s planes could “ be called in

a minute and then turn on a dime “.

In reality, it would not be until Korea that fighter -

bomber missions would actually have the capability to loiter

in an area waiting for a mission from ground controllers but

the XIX Tac Air, and its Army Air Corps companion units, IX

Tac Air and XII Tac Air supporting the balance of US forces

in the France - Belgium - Germany campaign, did much to

explore and advance the doctrine of close air support.

Success was a matter of intelligence, intense planning,

innovation and very close coordination with the ground

forces extending down to regimental and battalion

commanders. It took a while for the radios, doctrine and

training to catch up with what Wayland and his staff

realized could be a possibility.

To support the emerging close air support doctrine, American

industry produced vast fleets of aircraft designed

specifically for precision bombing at low altitudes.

Specialized medium bombers, the B 26 Marauder, a good

example, modified fighters, P 51 D Mustang and the ultimate

World War II US fighter - bomber, the P 47 Thunderbolt were

rolled out in fast fashion to meet what commanders demanded

. As new aircraft were approved for production and

deployment, pilot training at dozens of stateside bases

specialized in the specific skills of close tactical air

support flying. What they did not learn in Texas or

Tennessee, was quickly picked up in the field. It was,

nevertheless, dangerous flying, attacking at low speed,

often against well defended targets in almost all types of

weather. Causality rates among crews were high.

Of almost equal importance to the aircraft and trained

flyers was the need to have Army Air Force radio teams with

the lead echelons of combat forces who were thoroughly

familiar with aircraft capabilities, the language of pilots

and the ground commander’s plan of attack. O. P. Weyland

helped design and test what would become ground based

forward air controllers as well as the mobile staffs that

approved, routed and, on occasion, redirected the attacking

flights. Often times message traffic for critical missions

still had to pass through various levels of headquarters for

approval but the radios, dedicated telephone networks and

trained staffs made the system surprisingly responsive in

terms of World War II expectations. From the fight across

France to the Battle of the Bulge to the final victory in

Germany, division and corps commanders from General Patton

down consistently singled out Wayland, his aircrews and

staffs for specific praise.

That mid summer day in Bad Kissingen, Major General Wayland

was the guest of Lieutenant General Hoyt S. Vandenberg,

commander of the Ninth US Air Force with his headquarters at

the Kurstadt. This was the link that brought the air parade

seen over London, Paris and Berlin and a dozen now bombed

out cities in Germany to the otherwise sleepy town on the

Saale. With the war over, Wayland was to return to Fort

Leavenworth as the new Assistant Commandant of all Army

schools there. Vandenburg was slated for the position of

Assistant Chief of Staff of the Army Air Force in Washington

and he took the opportunity to honor his old friend and

former subordinate. At the air parade, both generals would,

at least symbolically, say farewell to their combat

commands. From the reviewing stand, eighteen months of

intense work flashed overhead in a terrible parade.

Less than a month later, Vandenberg relinquished command to

Major General Bill E. Kepner, former commander of the Eighth

Air Force in Germany. With the war over and Army of

Occupation plans moving forward, the only major Army Air

Force command slated to remain in Germany was the Ninth and

in many ways, it was being dramatically reconfigured for a

new mission. While some air assets would remain, the men of

the Ninth were to become part of the force policing post war

Germany and of particular note, they were tasked with the

search for secret Luftwaffe technology.

In later years, O. P. Wayland’s career continued with a

variety of significant staff and command positions to

include overall command of Tactical Air Operations in

support of US forces in the Korean war. He was responsible

for the building of the modern Japanese Air Force in the mid

1950s and received his fourth star. Weyland retired from

active duty in 1959 and died in 1979. He is acknowledged as

one of the founding fathers of American modern tactical air

support.

Hoyt Vandenberg left Germany and returned to Washington. In

rapid succession, he was assigned as the director of the

newly formed Central Intelligence Agency, the Vice Chief of

Staff and then Chief of Staff of the new, separate Air

Force. He died in 1953 after cancer forced a premature

retirement, however his name is forever recalled with the

military space and defense program located at Vandenberg Air

Force Base Rocket Missile Launch Facility in southern costal

California.

In Bad Kissingen, there are no official recollections of

this spectacular air parade although the memory of a sky

darkened by hundreds of low flying aircraft and the

accompanying engine roar must have lived on for some time.

The Saale Zeitung and other local newspapers were out of

print and would not resume publication until the late 1940s;

reporters may have made notes but there was nowhere to

deliver the story. With day to day needs of food and shelter

very much concerns even in the Rhoen, apparently even the

ever present German amateur photographers did not reach for

their Leicas. Likewise, official Army Air Corp photographers

also seem to have missed the event as there were no

surviving photos from the day. The shadows of hundreds of

over head aircraft soon left Bad Kissingen but interesting

shadows gathered for many months on near by valley floors

throughout Bavaria.

Look to the Valley, We Cover the Ground!

(II) Big Plane Reserve Rests in Germany - New York Times - 7

August 1945

Munich, Germany, 6 August - Kathleen McLaughlin -

Hundreds of Fortresses to Be Joined by Other Bombers, Many

Fighter Aircraft

Aligned wingtip to wingtip and nose to tail in precise

geometrical formations, a sea of B 17s unfold in an

impressive panorama around a bend in the highway that

stretches from Munich to Salzburg.

Hundreds of Flying Fortresses are concentrated on this

former Luftwaffe center and another 100 arrived yesterday.

More are to arrive within the next few weeks.

This is the largest reserve pool of heavy bombers in United

States occupied territory and it is an object lesson that

needs no interpretation to the tens of thousand of Germans

who pass here daily.

The lengthy article went on to explain that many of these

aircraft were delivered directly from other holding areas

and had in fact, never participated in actual combat, they

were reserve aircraft. Once that group was pooled, then the

combat aircraft units would likewise add their aircraft to

this area and others fields and lots nearby. A small group

of Army personnel were responsible for guarding the assembly

areas and the fate of the air armada was currently under

review. There was some speculation that the area would

become a training center for future pilots and crews.

>>

The victory air parades held by the Americans in the Summer

of 1945 had a secondary function beyond impressing war weary

Germans and saluting departing general officers. The parades

were used to help funnel US aircraft to central locations in

southern Germany for final disposition. Within days of the

end of the war in Germany, the War Department cancelled

thousands of defense contacts across the United States,

staffs worked over time to identify which troops were needed

in the Pacific, who might be released from active duty and

what to do with all that equipment that had just won the war

against the Fascists.

Manufactures who had been staffing factories at three full

shifts building aircraft for use in Europe were, upon

receipt of a single telegraph message, ordered to

immediately cease production and plan for a rapid return to

consumer oriented products. While the war against Japan was

yet to be decided, Washington had no further need for B17s,

P47s or dozens of other aircraft seen as not suitable for

the Pacific theater. Production lines stopped all over

America with a frightening efficiency. One shift left the

plant - no further shifts were called. In the Army Air

Corps, crews and support personnel not needed elsewhere,

were discharged as soon as possible; all of the aircraft

posed a particular problem.

The fate of thousands of aircraft that carried the best

American technology available at the time into European

skies is indicative of just how dramatic the shift to a

peacetime economy was planned to be. The same planes that

saluted dignitaries at a few select European locations in

the air parades, once landed, were pooled at huge collection

points in the American occupied zone in deep southern

Germany by men who reported to BG Frank Camm and his Office

of Liquidation, part of the War Assets Administration. Camm

would be the cutter and crusher.

Camouflaged or silvered wings gleaming in the late Summer

sun, they were parked wing tip to wing tip until heavy and

medium bombers, fighters of every type plus light aircraft

and transports paved entire valley floors in Bavaria

stretching to Austria as far as one could see. At the

beginning of the collection program, the Army considered “

moth balling “ the fleet for storage but under review, this

was deemed impractical - south German weather is not

friendly to outside warehousing plus, clear eyed planners

noted that the prop driven aircraft that won a European war

in 1945 were probably not in their thinking with the dawn of

the jet age. That left only one real alternative.

In most cases, the engines were first stripped out first, to

recycle the high grade steel and aluminum. The remaining

airframes were then torn apart, blown up, run over by bull

dozers or burnt in massive fire pits. What was left was

scooped up and sent to the regional smelters. A few months

later, similar bonfires burned across the Pacific consuming

a second American air war fleet. bonfires burned across the Pacific consuming

a second American air war fleet.

Local Germans observing these activities in the late Summer

of 1945 must have looked on with a sense of disbelief mixed

with war weary irony. First, the Americans had driven the

Luftwaffe from the sky and bombed Germany virtually at will

for months on end. Then, peace came yet they filled the

skies one last time with aircraft. Flying in massed

formations at low altitude, the sound was as though a

thousand locomotives were screaming past. A few allied

generals and politicians looked up and smiled; at least this

time, the Americans dropped no bombs. Finally, the

conquerors clogged roads, fields and valleys with miles and

miles of parked aircraft until the countryside could hold no

more and then … they burned their planes.

Hitler and Goering had promised that Germany would witness

the destruction of the attacking American air armada. For

southern Bavarians looking on from hill top wood lines in

September and October 1945, this prediction had very much

come to pass.

Look to your fields, We Predict the Weather!

(III) U.S. Weatherman to Aid Reich - New York Times - 26

July 1945 -

Drew Middleton

Bad Kissingen - Germany - 25 July - Reuters

One of the first moves to help Germany feed herself has been

taken by the Ninth Army Air Force, which is making its

continental weather service available to German farmers, it

was revealed today.

The Germans own service collapsed with the defeat of the

Reich, and this new measure will enable them to get long

range forecasts to assist their crop planting.

>>

In immediate post war Germany, for local agriculture to

resume feeding the German population, a lot of things needed

to go right. A fast release of POWs was necessary to work

the fields, seed and brood stock were required to jump start

production; the harvest of 1945 was a disaster and the

Allies were squabbling over who owned what, the amount of

war reparations to be paid and where the meager harvest

might go. It seemed as though the Winter of 1945 would be

one of politics and privation.

What to do about starving Germans was a vexing question in

Washington. Some argued that whether 10,000 starved or

100,000, it made little difference, they were all Nazis or

supporters and a harsh peace was the dividend of the war

they waged. On the other hand, the occupying forces saw

nothing but trouble. Lack of food led to an explosion of

black market activity and general lawlessness. In the French

and British zones, already feeding programs were underway

and in America, even though the horrors of the holocaust

were being publicized, there was no wide spread demand for

revenge once the European war was finished.

After some political debate, it was determined that the

American zone of occupation would not become a zone of

starvation, food supplies would be made available in true

emergency situations and a major effort was announced to

reestablish German agriculture by the Spring of 1946.

Of all aspects of German society that Americans explored and

assisted in during the immediate post war period, one of the

more important efforts yet seldom recalled activity was the

resurrection of the German Weather Service. It needed to be

rebuilt and from the Summer of 1945 thru 1947, the center

for these efforts was Bad Kissingen. In Washington, where

some senior officials said, “ let them starve “ … in

Germany, the Army Air Corps said, “ let’s reconstitute the

Weather Service so that the farmers can resume work . “

(IV) Germans in Weather Unit - New York Times - 11 January

1947

450 Now Employed in Stations U. S. Official Reports

Berlin - Col. Don McNeal, head of the United States

meteorology section here, reported today that German

meteorological services in the United States zone now

operated two forecasting centers, five secondary forecasting

centers, thirty - five synoptic observing stations, eight

mountain observing stations, fifty - five climatological

stations of higher order and 1056 rain and snow stations.

The organization, with headquarters in Bad Kissingen, has

450 full time German employees supervised by United States

officers. It has been built up in accordance with an Allied

Control Council agreement to set up zonal meteorological

agencies which later will be merged into one national

governmental service.

>>>

In the pre war years, Germany had a highly sophisticated

National Weather Service and with a central location in

Europe, it played a key role in collecting, processing and

passing on vital weather data to bordering countries. With

the coming of the Nazi state, much of this operation was

brought into the military with data collection and analysis

preformed by the Luftwaffe, Navy and the Army. From Berlin,

the information necessary for civilian activities, from the

weekend weather report to detailed farm related projections,

was then parceled out by appropriate government ministries.

Only the archives of the old weather service and certain

laboratory functions remained in civil hands. Some private

metrological research and data collection was performed at

schools and universities across the country and then shared

through academic circles.

Much of this was undone with the loss of the war.

Weather stations, records and equipment were lost or

damaged, trained observers, technicians and weather

scientists had been drafted, served on all fronts, and their

ranks were thinned by the war. In mid Summer 1945,

Eisenhower declared that efforts needed to be made to locate

as many trained German metrological personnel as possible in

the Allied PW camps. If there was to be a Fall planting in

1945, the crops needed to go in fast with agriculture

supported by accurate weather data. In the interim period,

the Army Air Corps would provide observations and

predications within its capability but a new German Weather

Service needed to be reconstituted.

In Berlin, the man tasked with the job in the American zone

was Army Air Corps Colonel Don McNeal working with the US

5th Weather Group. He had distinguished himself during the

war by creating the schools necessary to find and train

thousands of servicemen who would become the weather

observers, analysts and technicians supporting the global

American war effort. He was a 1934 graduate of Cornell with

a masters degree in geo and planetary sciences from Cal

Tech; he was the Army’s weatherman.

Under McNeal’s command were a pair of names that would

appear prominently in Air Force weather circles well into

the 1990s, Lt. Paul J Bodenhofer and CPT Richard M. Gill as

well as two German scientists, the Weickmann brothers,

Helmet and Karl. Gill had a particularly interesting task in

the immediate post war period. With a team of Signal Corps

personnel, he dashed across what would become the Soviet

zone in Germany looking for German weather stations and

stripping them of key instruments that were packed and

rushed back to the American zone. Bodenhofer, after

graduation from UCLA in 1938 with a degree in geo science

and atmospheric studies, had done graduate work in Germany

prior to the war and had met many of the top German weather

scientists of the day. His knowledge of both the language

and the personalities proved key in the early days of

reorganizing the weather service.

Helmet and Karl Weickmann were geo science university

professors who had spent the war in Germany and for the most

part, were not associated with the Nazi period of the German

Weather Service. They were on the “ Paper Clip “ list of key

scientists the Americans were rounding up and shipping back

to the United States but for about four months at the end of

1945 and into 1946, they were prominent in putting a “

German face “ on the rebuilding effort.

From the first stages of the project, McNeal knew he was

rebuilding an organization that should become a German

responsibility as soon as possible. His orders required

intense cooperation with the British and French zones of

occupation, represented respectively by a Captain Darking

and Lt Valade and technically, with the Soviet zone as well.

His counterpart there was Major Trupikow. An indicator of

things to come, coordination went fairly smoothly in the

West, it was another matter with the Russians.

Among demands from the Trupikow was that the new service

headquarters be located in Berlin, a reasonable request in

1945, that it be in the Soviet portion of the divided city

and ultimately, come fully under Russian jurisdiction -

these latter demands were totally unacceptable to McNeal and

his bosses.

The Americans at the Office of Military Government in Berlin

proposed that as the framework for the new German Weather

Service, seven regional data collection and analysis hubs

would be established. The English and French zones each

would have one major weather center and a corresponding

reporting network. The large Soviet zone likewise received

only one center, in Dresden. Four weather reporting centers

were to be in the American zone to include one in Bad

Kissingen.

As a compromise on the Berlin question, the Americans

proposed a significant German weather laboratory would be

established at Templehof airport in Berlin located in the

American zone of the divided city. The final location of the

new weather service headquarters was not specified but at

the time, the Americans did not foresee a permanently

divided Germany so Berlin was not officially ruled out. A

specified goal of the Allies was that as soon as practical,

the rebuilt German Weather Service hubs under the

supervision of the French, English and Russians, would be

merged with the American effort to create one of the very

first large post war German national bureaucratic

organizations. This was to be one, small but important early

step to a rebuilt German nation.

A Ninth Air Force Lieutenant named Peters was the chief of

the Bad Kissingen weather office. He was soon joined by a

former senior Luftwaffe weather specialist, Kurt Burger,

plucked from one of the camps along with a cadre of other

former PWs to work with Ninth Air Force counterparts. As

more local Germans with weather analysis experience were

found or trained, gradually the observation and analysis

network spread from the hub across the countryside.

Because the Americans were taking overall responsibility for

reestablishing the service and personnel from the Ninth Air

Force were very much involved, by the Fall of 1945,

Kissingen was named as the defacto headquarters for all

weather data collection in the American zone.

Just how much data came in from the British and French zones

is not clear, but these allies were eager to hand off many

post war requirements in their sectors to the Americans, if

for no other reason than to cut administrative costs and

responsibilities. It seems safe to conclude that in both

North Germany, the British zone, and the French occupied

Eiffel region of far western Germany, the reestablishment of

the hub and observer system using German personnel as much

as possible, followed the familiar American pattern.

In one of the many ways that early fracture lines of the

Cold War were slowly becoming evident, the weather data in

the Russian occupied zone was reported to Dresden and only

occasionally and in summary fashion, did Dresden bother to

report to Kissingen.

As more weather and climate trained German technicians were

located, the American presence in the weather service

steadily diminished with many of the Army Air Corps

personnel in Germany being released from active duty or

transferred to the 8th Weather Group being built up in the

Arctic. Records report that as early as the Fall of 1945,

Peters already had a staff of twenty experienced Germans

including several staff members with university level

training.

By the middle of 1946, with the exception of senior staff

members at Kissingen, an all German weather service had been

largely rebuilt in the American zone, with its offices on

several floors of a local Kurhotel pressed into service as

office space. The following year, the weather reporting hubs

and networks under English and French control were fully

integrated into the American zone network and US supervision

of day to day activities of the German weather service began

to close down.

In the Eastern Zone, the Russians had built their own

weather observation and analysis network, declared Dresden

the headquarters with little interest in sharing information

or further integration into a larger network. Even the very

air and clouds had taken on a decidedly East and West German

nature.

By 1954, the Central Office of the German Weather Service

was free of American supervision and relocated from Bad

Kissingen to Frankfurt once a sufficient headquarters was

built. Two years later, as the Federal Republic of Germany

came into being as a sovereign nation, the Central Office

relocated again to their current home in Offenbach.

During the 1950s and 1960s, coordination between the East

German Weather Service and its West German counterpart

increased in the interest of overall German safety. With the

reunification of the two Germanys in 1991, the Dresden hub

and its full network of reporting and observing stations was

finally fully integrated into the modern unified German

Weather Service..

>>

Returning to Bad Kissingen and the days of Daley Barracks in

the early 1980s, although the West German weathermen had

long left the town, Cold War politics was still very much in

the air and on the shelf.

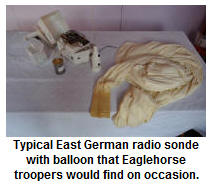

Prominently displayed in the Eaglehorse Squadron S2 office

was a pile of black plastic and aluminum bits and pieces in

a partially crushed cardboard box. These were the remains of

a Radiosonde, an East German weather observation instrument

that once had been carried aloft by helium balloon, then

drifted into squadron border area and crashed hard by a

road.

As I recall the story, these semi disposable devices were

launched by the weather services of almost all nations to

take simple measurements at altitudes in excess of 100,000

feet. What goes up, sooner or later, comes down and one or

two East German models per year were found by cavalry

troopers. By agreement, whatever was plucked from a tree or

found in a field was to be turned over to the BGS for formal

repatriation to the East, however, this one seemed to never

quite leave the office.

We used to joke that it was the perfect Trojan horse,

silently listening to all of our conversations and then

reporting back to Meiningen each night: the level of

pressure in the cavalry headquarters was high with extreme

amounts of hot air present in the conference room and that

regardless of the season, it was currently snowing at

Wildflecken.

September 2012

|

|