Where are Your Decorations?In early

2007, one of the major retailers of military

collectables placed for sale a significant lot of

medals, presentation certificates, formal paperwork,

badges, photos and other personal and military effects

related to Oberstlieutenant ( lieutenant colonel )

Rudolf Haen, a German Panzer officer from World War II.

Haen’s career began with the 2nd Panzer

Division and as the war progressed, he became one of the

highest decorated armor officers of the Reich. He

survived the war and somehow escaped from his last duty

assignment in Italy only to be shot by U.S. forces on

the first day of peace at a POW camp just outside of Bad

Kissingen. Much of his life is well documented, the

great mystery lies in the circumstances of his death.

To Die with the Coming of Peace

Oberstleutnant Rudolf Haen

The 3rd Infantry Division and the 14th

Armor Division cleared Bad Kissingen and the immediate

surrounding regions of German resistance in the first

week of April 1945. The city surrendered without

fighting, the last tanks of the famed German 2nd

Panzer Divison, once traditionally linked to this

Oberfranken region, were destroyed just north of Bad

Kissingen. The smoke cleared, the U.S. tanks and

infantry moved on and Bad Kissingen rapidly became part

of the XV Corps rear. The military significance of the

area was relegated to the bridges and major roads that

were still intact and how they fit the vast logistics

plan supporting the surging Army in the final days of

the war.

In tracing the specific threads of history related to

the American Army and Bad Kissingen during this period,

only fleeting reference is found to the Kurstadt. A few

rare citations mention an Army vehicle repair area and a

POW camp in the vicinity of the city; the specific units

responsible for these operations is unknown. At least

for the moment, which American unit ran the POW camp and

how a highly decorated German officer came to be shot on

the first official day of peace in 1945 is lost to the

fog of war.

The Army and the Army of Prisoners

From the first trickle of German POWs taken in the

opening hours of the Normandy invasion to the

unparalleled flood of prisoners encountered by

Eisenhower’s Allied Expeditionary Force in the last days

of the war, the record is clear that on the whole,

captured or surrendering German forces were treated

professionally and humanely by U.S. forces. There were

exceptions, particularly when members of the SS were

captured or, towards the end of the war, once the

horrors of the Nazi concentration camps were discovered

and became widely know among Allied troops. It was not

uncommon for newly liberated concentration camp victims

to take the law into their own hands for a few hours as

U.S. soldiers stood by. There also were isolated

instances of American soldiers roughing up, beating and

even executing captured Germans but these were not

sanctioned events and while not thoroughly investigated

or prosecuted, actions of this nature, when suspected,

were at the minimum, strongly discouraged.

U.S. Commanders and leaders at all levels were to

insure that prisoners were disarmed, interrogated when

possible for locally important information and then sent

quickly to the rear. Combat troops handed responsibility

off for POWs as soon as possible with battalion and

division support troops usually sheparding long German

columns to the rear. POW camps were the responsibility

of the Military Police within Corps and Army rear areas

but by the Spring of 1945, their numbers were stretched

thin by the sheer volume they faced and under utilized

units with no formal training in prisoner administration

increasingly were ordered to the POW task.

In central Germany, the number of POWs reached

proportions that began to strain the abilities of U.S.

forces to adequately process the vast broken army. The

Wehrmacht was dissolving and given the choice between

surrendering to the Americans or the Russians, the roads

and forests became choked with unarmed soldiers in gray

fleeing to the west - southwest to reach American

custody, hide in the woods or simply make their way

home. In the British sectors of responsibility,

surrendering Germans were often directed, led or chased

towards the boundary with U.S. forces. The numbers of

POWs were astounding and Earl F. Ziemke wrote in his

The U. S. Army in the Occupation of Germany 1944 - 1946,

“ the plans had anticipated U.S. prisoner of war

holdings to reach about 900, 000 by 30 June 1945. On 15

April 1.3 million prisoners were in U.S. hands. Another

600, 000 captures were expected in the next two weeks

and at least that many more in May. Legally they were

all entitled to the basic rations and quarters furnished

to U.S. troops of the same rank. “

At the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary

Forces, to help guard all the prisoners, additional

forces were allocated to include the men from most of

the U.S. anti - aircraft battalions deployed in Germany.

Open air camps holding tens of thousands of men became

the norm, the prisoners had no shelter beyond the tent

halves they may have brought with them. There was no

running water or sanitary facilities. Thousands would

have died of exposure were not for the late Spring of

1945 being relatively mild and the POWs were, by virtue

of long years of war, already familiar with Spartan

conditions and short rations. Logisticians tried to

insure that at a minimum, each POW received one C ration

per day . Camp administrators organized captured German

medics and doctors to form local POW hospitals overseen

by Allied medical personnel.

The search was on for a select, small list of Nazi

political figures and known war criminals but for the

vast numbers of rank and file POWs, the Spring of 1945

was spent staring out at the countryside separated from

the German woods by a few strands of barbed wire and the

U.S. guards. From the camps, it was not uncommon for the

prisoners to see, in the wood lines, groups of their

fellow soldiers, marching along in some loose order

heading home. American guards might give chase or allow

the bands to disappear into the forests. Maybe someone

else would pick them up. Such was the environment that

prisoner of war Oberstlieutenant Rudolf Haen found

himself in early May 1945.

The Career of Oberstlieutenant Rudolf Haen

By any standards, Oberstlieutenant Rudolf Haen was a

remarkable combat leader. He was born in Stuttgart in

1915 and began his career after graduation from the

prestigious Military Academy at Potsdam Berlin in the

traditional pattern of an enlisted soldier quickly

placed into the Junker - Fahnenjunker officer training

path. One source states his first assignment was with

the 5th Aufklarungs Abteilung, the scout

battalion of the 2nd Panzer Division, located

in the town of Kornwestheim. Other sources place him

during this period with the 5th

Kraftfahrabteilung, a motorized transportation battalion

headquartered in Stuttgart with companies in Ulm and

Kassel. This latter source is probably the more accurate

account; Haen, never married, maintained his official

home of record at a Stuttgart address. Either way, this

was all consistent with the beginning of a Panzer career

although, there is an interesting brief side story.

Apparently, Haen was fascinated during his career

with the German Army’s Fallschirmjagers - paratrooper

corps. The owner of Haen’s papers reported that found in

the collection were dozens of photos related to these

specialized Luftwaffe units and Haen, had he the chance

to restart his military career, probably would have

followed Luftwaffe General Karl Student into the

fledgling paratroopers. This was not an option in the

mid 1930s and it was with the dynamic Panzer forces that

he would make his mark.

By 1938, Haen had passed the probationary period, was

promoted to the grade of lieutenant and assigned as the

“ ordnance officer “ of the II Battalion, Panzer

Regiment 4, 2nd Panzer Division. This

position was similar to the U.S. battalion / squadron

motor officer with the additional responsibility of

maintenance and repair of all weapons associated with

the unit. It is unclear if Haen was with the battalion

while it was in Schweinfurt; he certainly was with the

unit after the move to Laxenburg, Austria.

With the coming of the war, Haen participated in both

the invasions of Poland and France while assigned to

Panzer Regiment 4. At some point, he may have served as

a tank platoon leader during these campaigns although

there appears to be no clear specific record. He

received the Iron Cross 2nd Grade for his

actions in the Polish campaign and was not decorated for

valor in the French campaign.

Haen’s combat career became particularly noteworthy

with the invasion of Russia in 1941. After service with

the 2nd Panzer Division, he was transferred

to Panzer Abteilung 100, a battalion assigned to the 47th

Panzer Corps operating in the central sector of the

Russian front and is awarded the Iron Cross 1st Grade.

The following year, as a senior lieutenant, he was

transferred to the 103 Panzer Battalion, part of the 3rd

Motorized Infantry Division. This armored unit did not

have tanks but rather was equipped with the highly

effective tracked assault guns that served the Wehrmacht

well in both attack and defense. Promoted to captain,

Haen took command of Company 1 and in September 1942, is

awarded the German Cross in Gold for valor during the

fight for Stalingrad. In November, he is again cited for

valor and received the Knight’s Cross. Wounded in

action, Haen was evacuated from Russia to recover in

Germany. The battalion he left behind was subsequently

destroyed over the next few months as the Soviets

encircled and eliminated the Sixth German Army at

Stalingrad.

In mid 1943, the 3rd Motorized Division

was reconstituted as the 3rd Panzergrenadier

Division and Haen, recovered from his injuries, was

given command of the reformed Panzer Battalion 103. The

division was sent to the Italian front and employed

against the Americans as they fought their way north

thru the mountains. In early 1944, he was promoted to

Major and in November, in recognition of his combat

achievements in both Russian and Italy, Haen was awarded

the Oak Leaf cluster to his Knights Cross. With this

level of award, Haen reached the upper echelons of the

German combat award hierarchy. After attending the

General Staff School in Berlin, in early 1945, Haen was

ordered to return to the Italian front as a member of

the Command Staff of the 14th Army. At this

point, the facts surrounding Haen’s well documented

career suddenly become very sparse.

The last entry in his military record records his

promotion to Oberstlieutenant effective on 20 April

1945. In Italy, the German 14th Army

surrendered on 2 May and the final line found in Rudolf

Haen biographies in English and German usually states he

was “shot “ or “ died “ in American captivity at Bad

Kissingen on 9 May 1945.

How does Haen get from northern Italy to central

Germany when virtually all German rail and air

operations had been destroyed is just one of the many

frustrating questions at hand. There still were a few

brave pilots with light aircraft ferrying the most

senior officials around what was left of the Reich in

the Spring of 1945. Combat record notwithstanding, at

his grade, Haen hardly qualifies for that type of

service and it is a very long walk in the snow through

the Alps from Italy to Bad Kissingen. Had Haen abandoned

the 14th Army earlier and somehow found his

way into Bavaria? This hardly seems in keeping with his

career that placed enormous value on loyalty to the

sacred German military traditions.

The owner of the Haen document collection speculated

that Field Marshall Albert Kesselring may have assisted

in Haen’s departure from Italy. They had know each other

in the Mediterranean front and Haen was a personal

favorite. In the last days of the war, Kesselring was

the Commander - in - Chief of Wehrmacht forces in the

West and certainly had the means to expedite Haen’s

escape. Whatever the circumstances, Haen, most probably

heading to Stuttgart, was scooped up by American forces

somewhere in the Main - Franken region in the Spring of

1945 and was sent to the closest U.S. POW enclosure. It

was located just outside of Bad Kissingen.

POW Enclosure Bad Kissingen and to Die with the

Coming of Peace

Beyond the fact that there was a POW camp at Bad

Kissingen, very little is known of its location, size or

the unit responsible for its operation. It was not at

the Kaserne or in the town, those facts are well

established and the Bad Kissingen city archivist has

nothing in his files related to Haen or the camp. The

one published German book that focuses on the war years

and immediate post war life in the town makes no mention

of the camp. The one camp in that area that does appear

in some detail in written accounts was located at the

Hammelburg, somewhat southwest of Bad Kissingen. As soon

as U.S. forces liberated the captured Russians and

Americans held at Hammelburg, the camp immediately began

to fill with German POWs.

Zeimke quotes the account of Lieutenant Colonel F.

Van Wyke Mason, a member of the SHAFE G 5 staff as he

reported a visit to a typical large POW enclosure

located near Bad Kreuznach in mid April 1945.

“ … I had a look at the jail that was well supplied

with Nazis and suspects. Then went on to the PW cage on

the edge of town. We arrived at sunset and saw a

breathtaking panorama; 37, 000 German, Hungarian and

other Axis prisoners roaming in a caged area of about

half a square mile. They certainly were not coddled

there. They slept on the bare ground with whatever

covering they had brought with them. They got two ’ Cs ’

per day and that was it. …there was a separate enclosure

for officers where they were so tightly packed they had

barely room to lie down and more trucks kept coming up

every few minutes … In command of the camp was a 1st

Lt of infantry with less than 300 ( he probably intended

to write 30 ) men. The boys looked a bit serious as they

crouched behind their machine guns for there was only

one strand of wire and no search lights for night time.

Periodically some Germans did try to get loose but they

were always cut down before they got 50 yards distance.

“

The camp at Bad Kissingen certainly was not this

large but Mason’s account describes a scene that in many

ways probably accurately reflected the situation that

Haen found himself in.

Which American unit in specific had responsibility

for this enclosure; yet another frustrating and

unanswered question. In the last week of the war, the 3rd

Infantry Division and 14th Armored Division

have long cleared from the immediate area. The post war

published histories of both units shed no light on the

issue and in the Main - Franken region, corps boundaries

and divisions within each corps seemed to change with

lightening speed even as the war was coming to an end.

Those post war accounts of U.S. POW operations in the

end phase of the war generally concentrate on either the

search for the war criminals or take the “ big number “

approach to the topic. With hundreds of un - named camps

and hundreds of thousands of prisoners, perhaps more

detailed accounts are just not possible.

I think Bad Kissingen lay deep in the U.S. XV Corps

area during late April, then on 2 May, the 99th

Infantry Division, part of III U.S. Corps, was ordered

to suspend its advance and pull out of the combat line.

Five days later, this unit was ordered to move towards

northern Bavaria and the area including Bad Kissingen,

and begin a formal occupation mission. Taking control of

the many POW camps and enclosures was one of their tasks

along with garrisoning of selected cities an towns,

safeguarding roads and bridges and a myriad of other

tasks. I do not believe they were fully in place,

however, by 9 May.

So how did Oberstlieutenant Haen die? Did he become

distraught at the announcement that Germany had lost the

war and challenged a jumpy and untrained guard? Did an

opening in the wire prove to be too much temptation,

then a mad dash and a blaze of gunfire? Did a guard,

during the sortation of prisoners by rank, discover that

Haen was a field grade officer and decide that one more

Nazi, alive or dead, just wouldn’t matter? Did he simply

die of exposure? This is all lost to history but perhaps

in the memories of a few old veterans who were there,

German and American, all facts of that day are recalled.

The exclamation point to the end of the war. Events

unforgotten because everyone remembered where they were

and what they did when they learned that the war in

Europe was over and that German or American, they had

survived. A day of prayers, laughter, black slapping for

some, for others, perhaps fear for the future. The 9th

of May was a day filled with so much that it could not

be easily forgotten. Memories to last a lifetime of

having survived the war, a story to be told over and

over again. And there may be one or two men living to

this day who also recall a vision of that day outside of

Bad Kissingen, of a camp, the barbed wire and the blue

sky and the story of one last man who died on a late

Spring day with the coming of peace.

By June of 1945, U.S. units involved with POW camps

were releasing tens of thousands of captured German

troops each week to ease the strain on care and feeding

requirements and insure that some level of local

recovery and in particular, farming, could begin that

year.

The Rudolf Haen collection of medals, badges, ribbon

bars, paperwork, diaries and photos sold for $ 11,

000.00 to a Spanish collector. They probably had been

kept at Haen’s home or by a relative and at some point,

still intact as a group, found there way into the

military collectables market. Between his globe trotting

job and other interests, the current owner is slowly

translating the Haen diaries and papers that perhaps at

some point, may will clarify at least Haen‘s last months

in Italy.

After the war, the remains of Rudolf Hain were

recovered and moved to an Austrian Military Cemetery in

Saint Johann, the Tyrol. Circumstantial evidence

suggests that the Veteran’s Association of the 2nd

Panzer Division was hard at work, recovering its honored

war dead.

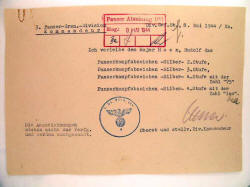

Documents authorizing lower levels of the Tank Combat Award.

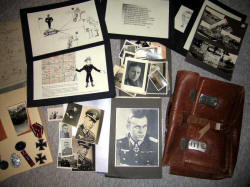

A marker in Austria and his decorations and papers fanned on

a desktop, Rudolf Haen, dead with the coming of peace.

Feb 08