|

The Army of

Occupation in Bad Kissingen and the Rhoen - Grabfeld Region

In May 1945, the war in Europe ended and there were no fewer than

1.6 million US soldiers in Germany alone. The tasks at hand were

organizing those thousands of companies, battalions, batteries and

sections, divisions and corps for either continued war in the

Pacific or return to the United States and discharge from the

military. Woven throughout the redeployment period were the

missions associated with the formal occupation of Germany, something

for which the rank and file in the Army had received little or no

specialized training.

The steady slog of daily combat and advance changed, overnight to

standing guard at farm trail cross roads, checking the papers of

thousands of Germans and central Europeans and taking some into

custody, allowing others to pass and then simply waving vast groups

along the trails, guarding against the potential last of the Nazis

while controlling smuggling between the German states. In pens by

the major towns, captured Germans soldiers were collected and the

rations were always dangerously short. Selected units were fast

down the trail in search of Nazi technology while Army legal teams

poured over documents and created lists of significant war

criminals. There were so many American soldiers and so many

problems in Germany - the Summer of 1945 was a period of

anticipation slowly turning to discontentment.

Around Bad Kissingen and the Rhoen - Grabfeld region, the border

area that Eaglehorse troopers might recall, it was a busy Summer and

Fall. Here is our attempt to provide a glimpse of this part of the

story of the Americans, the Germans and Bad Kissingen.

The Fog of Peace

After a period of significant troop movement, adjustment and

readjustment in the Rhoen area, long after the 3rd Infantry Division

and the 14th Armored Division had stormed through, the dust had

settled by mid Summer and fragmentary evidence begins to turn up as

to specific units, locations and activities. This takes into

account those divisions of the VIII Corps that had attacked north -

northeast across the old German state lines of Bavaria into

Thuringia and then were in the vicinity of Meiningen.

The 99th Infantry Division had initial occupation responsibility in

the upper and lower Franconia region with the 79th Infantry Division

also moving into local assembly areas. Which other units followed

and their significant experiences is unknown. It was an extremely

fluid environment, almost all divisional histories of that era end

on the first official day of peace but now and then, a document

turns up and a stray battalion can be traced to a familiar town. It

might seem safe to say that the parent Combat Command, basically the

brigade combat mix, would have been nearby but this was not always

the case. Some units were consolidating for movement while others

remained spread across large geographic areas. One clue is that the

Military Government ( MG )Teams, so crucial in re establishing

immediate post war order to Germany, were generally matched to

divisions tasked with the first days of the occupation and this

single thread can lead to understanding troop dispositions.

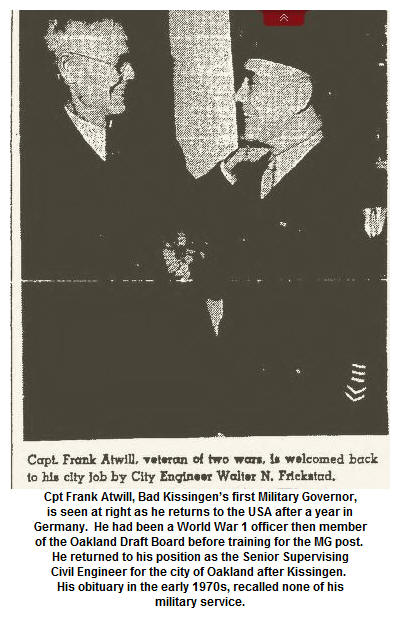

MG teams attached to the 99th Infantry Division fanned out to

Schweinfurt, Munnerstadt and team I2A3 led by a Captain Atwell,

moved into Bad Kissingen. But only a few miles to the north, MG

teams in Bad Neustadt and Meiningen, were attached to a different

and unidentified division. They may have been supported by the 79th

Division or some other unit, there is just no available evidence.

It was a Summer of great activity and some progress. The old state

border region between Hesse, Bavaria and Thuringia - what would

become the Cold War border, had been earlier discussed as a

convenient line between the Russians and Americans. US forces, in

the heat of the campaign, had penetrated as deeply as 250 KMs

intoThuringia and Prussia and when the fighting stopped, and

everyone caught their breath, certain readjustments were

necessary.

American forces that had ended the war and then remained in place

north of what was rapidly becoming more of a border and less of a

simple line on a map, were withdrawn south into Bavaria in mid

Summer 1945. The American military government teams that had been

stationed in Meiningen and similar surrounding towns, were likewise

withdrawn and control handed off to the Soviets. But this is not to

say that the Americans left empty handed. Whether it was the search

for looted art and Nazi science and technology, picking up war

criminals or just cleaning our the banks - the American Army insured

that the trucks were full as they headed south. The first sunny

days along the new border between the German states were marked by

handshakes, smiles, trading vodka for cigarettes and both Russian

and American MPs waving the military traffic through while trying to

first manage and then prevent the German population from following

the convoys out of the region.

For soldiers not otherwise engaged with the occupation missions of

security, civil control, or administrating to hundreds of thousands

of German POWs, and this was the vast majority of US forces,

commanders took up the available time with intensive unit sports

programs, inspections of men and equipment and, when all else

failed, sight seeing tours. The USO and Special Services Division

were active with entertainment and running excursions, anything to

divert troop attention from German women and venereal disease, a foe

portrayed as dangerous as the last German soldiers battling from the

final trench.

A Certain Clarity and

a First Mission at the Border

By mid Summer, references to specific units and missions can again

be found. The town of Bad Kissingen and the immediate surrounding

area was a 9th US Army Air Force responsibility. Rapidly shedding

the many fighter and bomber groups, logistics and maintenance units,

the Headquarters and Headquarters Squadron augmented by a huge staff

support section moved into the downtown area with their 926th

Signal Battalion and the IX Air Defense Command plus other

unidentified units in and around nearby Bad Neustadt. There may

have been other 9th AF units in the area, close aircraft squadrons

were identified in Schweinfurt and Wurzburg but references to the

926th Sig and IXth.ADA units are frequently found in multiple

sources.

The IX Air Defense Artillery Command was particularly active in

getting the names of soldiers receiving awards, as well as brief

articles recalling unit activities, into local US newspapers and

this example illustrates what probably was a common soldier

experience.

Iowa Globe Gazette

July 15, 1945

“PFC Charles Sorlien, son of Mr. and Mrs. Oscar C. Sorlien, 415

Georgia St. SE is at present stationed at Mellrichstadt, Germany

according to word received by his former associates in the

compositing room of the Globe - Gazette. He writes that he works on

a switch board from 8 until 11 each morning and during the same

hours at night. The rest of the time, he says, is his own. He says

he has seen Jack Benny at Schweinfurt and the Glenn Miller Band. He

has seen quite a bit of the countryside, going out in a jeep almost

every day. Some of his other spare time was used operating the

movie projector for the unit, he wrote. “

Other articles recalled the trips across Germany made by Lt Leslie

H. Mckensie, the 9th Army Air Force Reenlistment Officer as he

convinced draftees to consider Army careers and the efforts of 9th

ADA Command Chaplain, Floyd S. Smith, to help the locals in Bad

Neustadt reestablish a local synagogue.

Beyond the newsprint, the 9th Air Force staff was tasked with a wide

variety of missions, everything from monitoring the weather and

reviving agriculture throughout the region to the search for

significant Nazi technology. On the one hand they were compiling

unit histories and disassembling the fighter and bomber commands and

across the hall - coordinating with German agencies as soon as they

could be stood up to insure some sort of transition from war to

peace without chaos or starvation in the immediate region.

Following soon into Kissingen some months later, with an interesting

back story all their own came staff units of the HQ XII Tactical Air

Command and although the evidence is sketchy, they may in fact have

established a local military school to retrain air personnel as MPs

to secure local areas and this begins to hint at how airmen became

occupiers in and around Kissingen in 1945.

We also find an interesting early snapshot of what was going on at

Manteuffel Kaserne on the hill above the town from about this time.

A personal recollection by a trooper assigned to a signal unit of

the XII Tac Air recalls that as his unit was being reconfigured,

they drew jeeps and trucks from a vast collection of vehicles lined

up in depot storage on the parade grounds of the barracks.

Apparently, as the 9th Air Force units departed Germany, their

vehicles and perhaps those from other units as well, were pooled at

Manteuffel and then made available to other units.

And then beyond the barracks gates, the first occupiers in the

countryside, the 99th Infantry Division soon departed for America

and assistance to the local MG teams became an ad hoc arrangement

probably informally tasked to the local air corps units. But the gap

was soon filled as units fully committed to the occupation mission

were identified.

In October, the US occupation situation in the Rhoen - Grabfeld is

well documented. The 3rd Infantry Division was withdrawn from

northern Austria where it had ended the war and then spent the

Summer. After a very brief stay in the Frankfurt area, it received

a new mission to occupy portions of south central Germany, the same

general region it had fought through some months earlier. The

specific zone, the Main - Franken area, encompassed in the south,

Schweinfurt and Darmstadt and extended in a box as far north as the

city of Kassel. Even for an infantry division, this was a large

area to garrison.

Around Bad Kissingen and the near border region, the immediate tasks

fell to the 15th Infantry Regiment, then placed under the

operational control of the 1st Infantry Division, the next major

combat command dedicated to the occupation, located to the

southeast.

From this period, there are some known unit locations for the 15th:

Regimental Headquarters at Schweinfurt, Service Company at Wurzburg

and the Cannon Company at Maroldsweisach. The First Battalion was

at Wildflecken with D Company at Elsenfeld. The entire Second

Battalion was at Hammelburg. Third Battalion Headquarters was at

Mellrichstadt, Companies L and M garrisoned Koenigshofen, and then

continuing northwest along the border, K Company was located at

Ostheim and I Company moved into Fladungen. Interesting to see that

Bad Kissingen was not at all in the garrison plan. While airmen

may have ruled the city, the very first men to the border came with

few jeeps, rather, 2 ½ ton trucks and combat boots were the choices

at hand. The border was in the hands of the infantry.

By the time the 3rd Battalion, 15th Infantry was in place north of

Bad Kissignen, they were not alone on the border. To assist in

Bavaria, the Americans had allowed a new civil Bavarian police

force to be established specific to the border area and this was

very much the work of the Military Government teams seeking German

solutions to German issues.

Retaining German police in the cities and towns had been an obvious

choice and required little effort but allowing a new force in the

border region was a significant step along the line towards an

official demarcation. These squads, consisting of former German

soldiers and armed with pistols, opened offices in dozens of

villages and towns along the border. Most offices were staffed by

small groups of ten or fewer men and were specifically to address

civil control in the border area. The Germans conducted many of

their patrols jointly with US occupation forces. And when it came

to actual strife along the border line, more often than not, it

involved German police based in the East and West - clashing. The

Russians had quickly responded with their own East German version of

a border police. With so many checkpoints and groups of smugglers

and displaced persons still on the move, and the border still

essentially open, clashes were bound to happen.

In the forests and rolling farm land that characterized the border

area north and east of Kissingen, the men of Companies L, M, K and

I would have spent much of their duty day in regular contact with

groups of wandering civilians. On the one hand were the refugees,

Germans who had for whatever reason, lost their homes or were

otherwise on the move. The second group was defined as displaced

persons. These DPs were homeless non Germans, streaming along roads

and trails after walking away from Nazi slave labor camps. Both

groups posed significant problems for the infantrymen who had

received no training for this mission.

US Occupation Troops

in the Rhoen - Grabfeld and German Refugees

Clearly, most Germans feared occupation by Russians and with the

American zone so close, thousands were willing to become refugees

and abandon their homes and run to the south and west. The

Americans were hardly able to provide for the resident population

within their zone let alone allowing the numbers to swell by tens of

thousands. Likewise, the Russians, who were rapidly flushing German

populations out of Western Poland and similar regions, saw only

problems in rebuilding their zone of occupation if the native

population fled. Both sides agreed that the flow should stop.

The initial US policy was to apprehend and return to the East, those

who were trying to flee and in one of those twists of fate, senior

American officers speculated that Russian and American troops would

come to share the mission of keeping German refugees from fleeing

the Russian zone into Bavaria and Hesse. While numbers and other

hard evidence are hard to come by, it seems clear that for American

infantrymen and their German police counterparts from Fladungen to

Coburg, a common part of any day would have been asking for the

papers of Germans found on the run.

Initially, those civilians moving in the border area with the new,

American issued ID papers indicating some tie to the region, might

be allowed to move on and this was a boon to those who had gotten

their papers from American Government Teams in Thuringia prior to

the early July departure. Those without papers or with papers from

the Nazi period indicating their homes were in Thuringia, might be

taken into custody or, more probably, escorted back to the open and

frequently poorly marked border and ordered to march north under

penalty of arrest. So of these groups of hapless refugees who were

turned back - many ran into the woods and tried again.

In the early fall of 1945, some of the features that would come to

be associated with the border area came into existence. Both US and

Russian forces began to mark trees and wooden stakes with paint to

indicate the physical border. The Russians with their own newly

created East German border police began to close roads and trails

with barriers, set up guard shacks and run single or double strands

of barbed wire in open areas. The major road running north from Bad

Kissingen to Meiningen and crossing the border by Eussenhausen

remained open but under close supervision by American and Soviet

troops. There was some commerce along the normal roads but

Americans and Russians agreed that what was produced in the states

of Bavaria or Thuringia should not cross state lines. The refugee

steam was somewhat stemmed, and the border barrier system began.

Interestingly, at just about this period, the quality and

professionalism of the US soldiers in the region and in fact,

throughout Germany, began to deteriorate. The war with Japan had

ended and remarkably, the Army, under orders to begin a massive

reduction in costs and personnel, began to send to Europe, troopers

who had received only basic training. Units tasked with the

occupation mission came to consist of veterans who desperately

wanted to go home and recruits with at best, marginal training.

US policy towards fleeing Germans changed in 1946. Along the

border, the Russians were adding bunkers and guard shacks and

relations with the Soviets were becoming increasingly tense. By the

second year of the occupation, as American soldiers picked up

fleeing Germans in the border region, they turned them over to the

local border police officials as soon as possible. The Bavarian

Border Police reported that in 1946, they had encountered 481

people fleeing from the East in the Rhoen hills and apparently

allowed them to move on or had directed them towards relocation

assistance. This number is probably only a small fraction of the

number that slipped through uncounted. Along the entire German

border between east and west, by 1948, an accepted number is that

over 700,000 persons had fled to the west. As borders go, it was

well guarded and porous, at least when it came to the Americans.

Occupation Forces and

Displaced Persons

The second large group of people that members of the 15th Infantry

would have encountered while on occupation duty in the Rhoen in late

1945 and well into 1946 were part of the hundreds of thousands of

displaced persons wandering the countryside, primarily former slave

workers imported by the Nazis from the east into Germany during the

war and now adrift in the countryside. While refugees tended to be

found in small family groups, the DPs traveled in bands sometimes

numbering in the several hundreds. They clogged roads, there were

health and sanitation issues and incidents of revenge taking against

local Germans were not uncommon. The larger DP groups could even

create significant local crime waves. Many of these people had no

interest in returning to nations now occupied by Russians but they

had no where else to go.

To deal with the problem, the Americans set up camps including a

huge one at the former Nazi barracks at Wildflecken and Army

humanitarian efforts in this regard can largely be summed up as:

round them up, ship them to camps, sort them out and then rail load

them home. Whether or not they wanted to return to the east was

not, at least initially, given much consideration. The Army’s

handling of the DPs was increasingly viewed as both ham handed and

sadly efficient in the pre Constabulary period.

Actual administration of the refugee camps was by 1947, handed off

to the International Refugee Organization that had moved its

headquarters into Bad Kissingen and this was a major turn in both

the politics of the problem and compassion towards the refugees.

Local camp police were formed, drawn from the throngs of DPs and

this freed the American Army from many of the dreary issues

surrounding the day to day guarding and administration of the camps

but even in the Constabulary period, massive raids by US forces on

the Wildflecken Camp were common in an effort to maintain order or

at least compliance of a population with no desire to return to the

East.

The IRO, to their great credit, worked tirelessly to resettle the

former slave laborers in the West if they refused to return to

countries now run by Communists and even West Germany, at the time a

minority share holder in the discussion, was not adverse to

regulated re settlement and offered a sort of second class

citizenship. American soldiers may have been the first camp guards

in 1945 but there were remaining echoes of this part of the

occupation mission well into the 1980s.

American troopers at Hohenfels, Grafenwoehr and Baumholder might

recall encountering personnel from range labor companies consisting

of middle aged men who spoke only Polish or Hungarian, while drawing

tents, targets or Saab target mechanisms. These men were the

residue of the thousands of displaced persons of the immediate post

war Germany. Having been allowed to remain through one of the

humanitarian programs and rather than being forced onto trains

heading east, these men were given a special status, neither

immigrant or resident, grouped into labor battalions and provided

jobs in support of the major American training areas. They labored

on until the end of the cold war coincided with their retirement and

the chance to return to the newly freed east or slip into the

German social safety net.

For the men of the Third Infantry Division and the 15th Regiment in

the Bad Kissingen border area, the occupation mission ended in mid

1946 with unit redeployment to the United States. There is very

little specific information related to these men and their

occupation period in the Rhoen. Historians agree, however, that on

the whole, in the last months of the occupation period, all across

Germany, American morale and trooper conduct suffered significant

breakdowns for a variety of reasons. The war was over - the

soldiers wanted to go home and there were other concerns.

The occupation forces were spread thinly over large geographic areas

and housed not really in barracks but in tents or commandeered local

German housing, this led to breakdowns in command supervision and

communications. There was a perceived lack of clear mission, poor

quality replacements, a lack of social services for the troops as

USO programs were cut back and unhappiness among the war veterans at

being retained in Germany for so long.

Many of the junior officers were likewise poorly trained or, had

returned to Germany after failing to find employment in the

peacetime economy. Due to boredom and a lack of active command

interest, there was excessive drinking, this led to rapes, shootings

and other crimes directed at local Germans who in turn, openly

brawled with American soldiers on pass. One of the regional hotbeds

for anti American sentiment during this period and an area noted by

significant unrest was in and around Coburg.

The very first Americans to the Rhoen border, flush with immediate

post war excitement, were faced with throngs of homeless people,

Germans, Czechs, Poles, Hungarians and countless others. There

were smugglers and Communists, POWs and peasants, wanderers in a

vast population on the move and an Army not well suited to the

mission. These units did their best to stand down from the combat

pace while taking on responsibilities for which they had no training

and all the while, the units were rapidly losing veterans to be

replaced by recruits. The scant evidence indicates the troopers by

and large did a credible job and when units began to break down on

the mission, they were soon given a much deserved return to the

United States.

Kissingen and then

the Border

At Kissingen, the 9th Army Air Force officially decamped with one

final awards ceremony on 1 December 1945. Select staff sections and

the HQ XII Tac Air remained for some further months before the last

hotel buildings in the town were returned to the German control and

the International Refugee Organization moved in to finally unsort

the many issues related to the displaced persons found in camps

across Bavaria and Hesse. The town and the barracks at Manteuffel

Kaserne were momentarily mostly free of Americans. But in the

fields and the hills to the north and east, there was that sound of

Jeeps running in the night, American soldiers with maps leaning

forward, peering down the trail and ready for what waited in the

darkness: anticipation, readiness and resolve.

The next to the border came forward with dash, élan and esprit de

corps. The next to the border in Rhoen - Grabfeld, were the

boisterous boys in jeeps with the Circle C Lightening Bolt insignia

of the US Army Constabulary.

Notes:

I have worked on this piece for months and keeping track of specific

notes for each fact / sentence was not fully done. The major source

points are listed below and if anyone wants a specific citation to a

sentence or paragraph, please contact Randy and I will try and

reconstruct the appropriate source.

US occupation of Meiningen and surrounding areas

Major source areas:

Come as Conqueror

Franklin M. Davis Jr.

Macmillan Press 1967

U.S. Army in the

Occupation of Germany

Earl F. Ziemke

Center of Military History

The American

Military Occupation of Germany

Oliver Frederiksen

United States Army Press 1953

Numerous period

newspaper and magazine accounts.

|